BONSAI '98

ROLES

YEAR

2024 - 2025

TIME

In Active Development

TEAM

TOOLS

2024 - 2025

In Active Development

Bonsai '98 started out in early 2024 as a shop management game, with the initial focus on crafting a detailed and immersive simulation experience. However, as development progressed, we recognized the need to pivot the design direction to better align with the scope of our resources and timeline. This shift allowed us to refine the core gameplay and ensure a polished, cohesive player experience.

As the lead designer, I have been deeply involved in shaping the gameplay mechanics and logic that form the foundation of Bonsai '98. From conceptualization to implementation, my role has centered on translating ideas into tangible systems that engage and challenge players.

This has also included navigating the complexities of preparing for a Steam release. Which has been a valuable learning experience, providing insights into store page creation, audience engagement, and the logistical considerations of publishing a game on a global platform. To me, Bonsai '98 represents a commitment to delivering a unique and memorable experience for players.

At the start of production, Bonsai ‘98 was something very different. Me and Mukund Narayan had gotten together in hopes of creating a project that would showcase our system design abilities and how we would be able to reuse systems in future projects. We’d originally thought of Bonsai ‘98 as a shop management game. One where you as the player would take care of your plants in a realistic manor, watching them grow and even manipulating the plants themselves. We’d started outlining all these deeper systems that would be at play simultaneously. We felt that players needed them to be captivated.

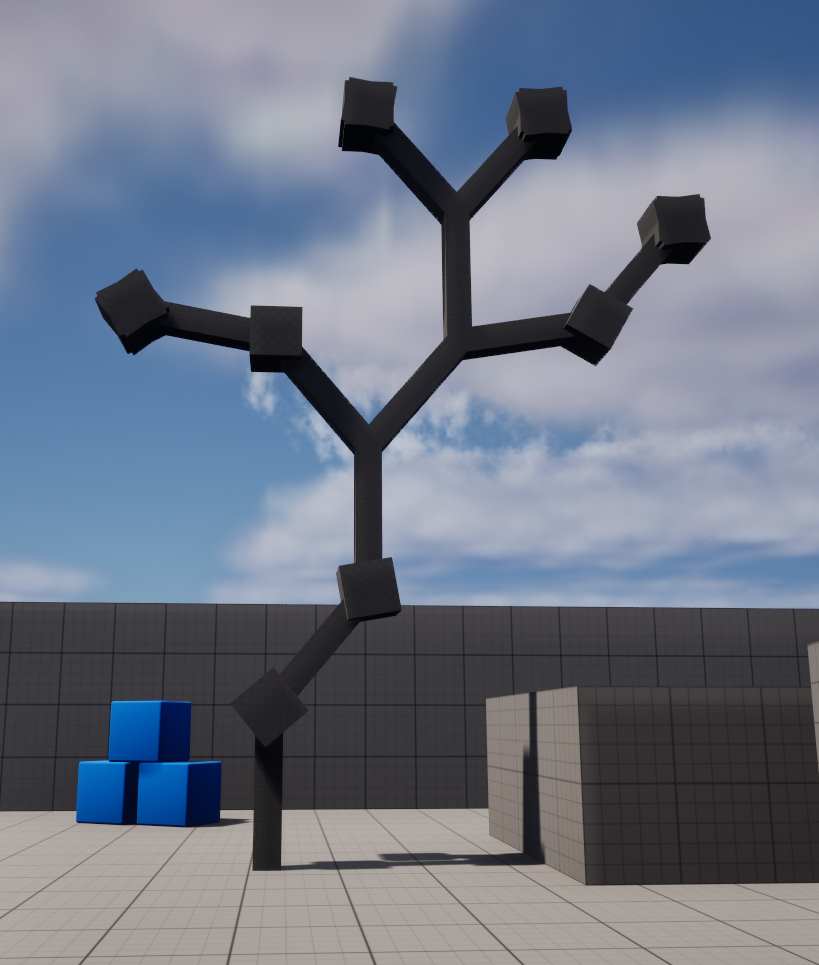

When we first showed the growth system to some of our other colleagues, we had what could be described best as a “wow” moment. We found in spite of everything that people were content, even without any real game mechanics, to just watch their plant grow! People were glued to the screen for a solid 10 minutes, just watching some digital plants grow. I knew this was it.

While we’d continued working on our original vision for some time, it started to feel that we had overscoped, and not only overscoped but that a majority of the features we’d been ideating didn’t actually align with what players wanted. I had started thinking about how we could condense the experience to capture the true essence of what actually captivated people.

Bonsai ‘98 got refined into its bare core, not a shop management experience, but rather we distilled it all the way down to the growth system itself. From there we realigned our pillars into three core pillars:

- Serenity : Enjoying the calm and fulfilling fantasy of tending to your beautiful bonsai.

- Self-Expression : The scene is yours to unleash your creative vision.

- Curiosity : Master the synergies between the mechanics and see what you unlock next.

We redifined the game as a pure sandbox exprience, allowing us to shift the focus to our core unique selling point of the procedural dynamic growth system.

A standout feature of Bonsai '98 is its dynamic procedural growth system, which has been a cornerstone of the game's vision since its inception where we’d envisioned giving the player freedom to shape and affect their plants and their growth. The system serves as the game's primary Unique Selling Point (USP), setting it apart from other titles in the genre. Entirely implemented in Blueprints, the growth system allows for a high degree of scalability and quick tweaking & editing.

A key goal of the system was for plants to be able to grow regardless of the root start position, even on uneven surfaces. On top of that we also wanted certain plants to have the ability to climb surfaces as well.

By designing the system to be modular and to be able to adapt dynamically based on each pieces properties, we achieved a level of flexibility that enhances the player experience and allows players to push their creativity further, as well as allowing us to quickly add, iterate, and even hotswap parts on plants.

One of the most exciting challenges in developing this feature was ensuring that it'd be performant. This was a bit of a challenge as everything was being created using Unreal’s blueprints and on top of that I’d never quite created a system like this.

So a growth system that also allows every part of it to be manipulated and even pruned by the player, great! Now where do you even start?!

I ended up conducting a fair bit of research into not just how other titles handle growth mechanics in general but I also studied real world plants, for example the Lindenmayer system used for describing plant growth, or how their stems split, where and why they split, the consistency of plant specific patterns and their exceptions, and more.

I’m very passionate about plants and I’ve always been fascinated by them and the mechanics behind their growth. I’ve been growing and taking care of plants for a few years and as we’d started development in early spring of 2024 this gave me the perfect opportunity to study plant growth first hand.

I’d purchased a variety of plants, such as various chilis, wild strawberries, and even a wisteria sapling of which all were very interesting to observer and to note their various growth patterns and common features.

Every week I’d make it a routine to check on their growth and to note any potential distinguishing features, such as the ability to see on chili plants (as well as others) and primarily their stems where new “nodes” could be found that allow the plant to grow both new leaves as well as branches.

Early on I’d looked into the way a majority of games handle plant growth, for example mesh swapping or shape keys. But none of these satisfied me in terms of their flexibility. We wanted something more, something truly unique and special.

When I noticed those “nodes” on my chili plants I got a sort of eureka moment. I knew this was exactly what we needed! The only thing that remained was the implementation.

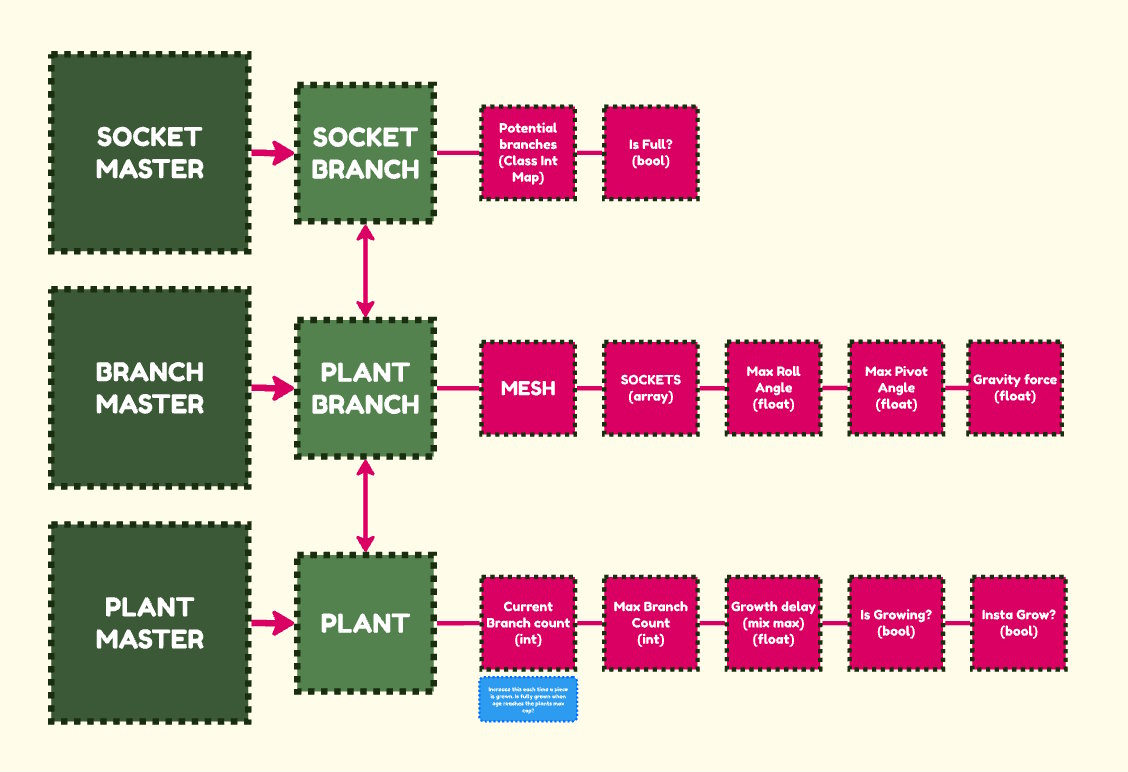

The growth system is built around three key actors that work together to create dynamic and scalable procedural growth that mimics real plants to some extent.

- The Plant Master serves as the core of the system, managing overall growth logic and overseeing the construction of new branches. It stores crucial variables such as the total branch count, ensuring that growth remains balanced and controlled.

- The Branch Master is responsible for self-managing the individual growth behaviors of branches. It accounts for factors such as gravity, and growth direction while also handling pruning logic.

- The Socket Master governs the probability and placement of new branches. By determining where branches should emerge, as well as which branches have the possibility of spawning.

These three actors communicate closely to maintain seamless procedural growth. The system primarily uses Blueprint interfaces for actor interaction while also utilizing direct access to relevant data when necessary. This structure not only keeps the system modular and adaptable but also enables quick modifications to the underlying logic. Additionally, the setup allows for the easy introduction of specific plant and branch variations, giving us the flexibility to fine-tune growth behaviors and expand on unique mechanics as needed.

The Plant Master serves as the foundation of the entire procedural growth system, acting as the core component that governs the creation and management of all plants in the world. It functions as the base structure, overseeing the initial placement and overall growth of the plant.

One of its primary responsibilities is storing key general values for its respective plant, including the total branch count, an array of available empty sockets, and variables such as growth speed.

When a plant base is placed into the world, whether through the editor or dynamically at runtime by a player, the default plant base socket is populated. At this point, the Plant Master initializes growth by attempting to construct new Branch Master actors until the plant reaches its max branch cap.

Additionally, the Plant Master is responsible for locating available empty sockets and signaling them through interface calls. This process instructs sockets to begin selecting and spawning viable branches based on predefined probability factors.

By centralizing core tree management within the Plant Master, the system remains flexible and modular, allowing for easy adjustments to growth logic, balance changes, and future expansions with new plant variations.

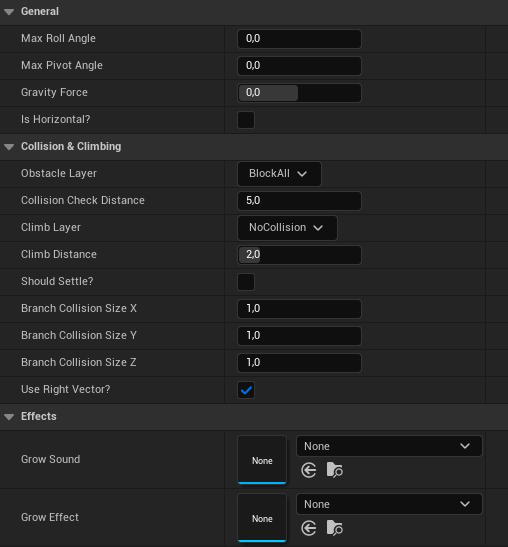

The Branch Master is the most complex component of the growth system, responsible for managing various growth behaviors, including gravity effects, climbing logic, root settling, and pruning mechanics.

When a socket instructs the Branch Master to spawn a new branch, the growth logic executes in a series of distinct steps to determine the final orientation of the branch:

1 Initial Alignment – The new branch is first aligned with the direction of its parent socket, ensuring that it extends straight relative to its origin point.

2 Gravitational Influence – The branch is then rotated toward the world’s Z-axis up vector, with the adjustment applied positively or negatively based on the desired gravitational force for that specific branch. This is achieved through lerping, allowing for controlled variation in how gravity influences different branches.

3 Randomized Rotation – To introduce natural variation, random rotation is applied across all three rotational axes, preventing uniform and unnatural growth patterns.

4 Settling Logic – If the branch needs to settle, a series of raycasts are fired to detect nearby geometry. This data is then used to align the branch mesh to surrounding surfaces, moving it closer to objects like rocks or the ground to for example achieve natural-looking root placement.

5 Climbing Behavior – Climbing uses similar sampling methods as settling, allowing the branch to rotate and align itself with nearby surfaces while maintaining a slight offset. This enables branches to grow along walls or rocks, effectively simulating natural climbing plant behavior.

6 Final Collision Checks – At the end of the growth process, a collision check ensures that the branch does not intersect with unwanted geometry, preventing unrealistic or broken placements.

The Branch Master is highly customizable, allowing for fine-tuned control over how branches behave. It includes settings for:

- Collision layers to determine what objects branches can interact with.

- Max deviations in roll and pivot angles to introduce variation.

- Gravitational force influence to adjust how strongly gravity affects growth.

- Growth constraints and logic overrides to modify behavior for specific branch types.

The Branch Master also manages pruning mechanics, ensuring plants can dynamically respond to environmental changes. When a prune interface event is triggered via an interface call:

1 - The branch identifies and marks all connected child branches and sockets.

2 - The marked branches and sockets are deleted, effectively removing sections of the plant.

3 - The Plant Master is notified of the changes, updating its socket availability to allow for new branch growth in cleared areas.

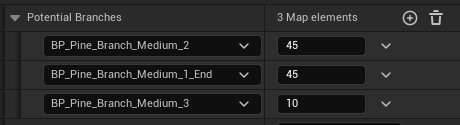

The Socket Master serves a straightforward yet essential function within the growth system: it acts as a potential growth point, determining what branches may spawn and handling the probability of their appearance.

When the Socket Master receives a construct branch interface call, it initiates the branch growth process. This occurs within a limited number of max attempts, ensuring that the system doesn’t get stuck trying to generate an impossible structure.

Each socket contains a dictionary (or map) of all possible branch classes that could spawn from it. This includes leaves, roots, or different branch types, each with an associated probability value. This probabilistic approach allows for varied and organic-looking plant structures, as different sockets can have unique probabilities for a varied set of branches that are set by hand.

The process unfolds as follows:

The socket iterates through its branch probability dictionary, attempting to spawn a branch based on predefined probabilities.

If a valid branch is successfully created, the socket signals to the Plant Master that it is now occupied.

The Plant Master then removes this socket from its list of available growth points, ensuring that it is not used again for further growth.

By leveraging probability-based spawning, the Socket Master allows for highly customizable plant structures. Designers can:

Define specific sockets that produce roots, leaves, or unique branch variations.

Adjust spawn rates for different plant sections, making some branches rarer than others.

Ensure controlled randomness, balancing procedural variety with structured plant forms.

One of the initial concerns we had regarding the creation and use of this system was how we were going to go about saving users plants and their creations. Saving these things was of course vital to making the gameplay work.

At first I wasn’t quite sure how to approach the problem. I’d never implemented proper saving into a game before, let alone a procedural growth system with multiple components that had to interplay correctly in a specific order.

But after taking some time to think about the problem and doing some quick research I was confident I’d got a fairly decent solution. Since everything within the game is contained in your pot that you create your scene within I could simply assign IDs to each actor in the hierarchy and also keep track of each actor’s parent’s ID as well. This effectively allows me to reconstruct the entire scenes hierarchy as needed.

To start, when creating any new actor, be it a prop the player can place or a new branch growing on the tree we simply generate it a new Globally unique identifier (GUID). When we eventually need to save the player's diorama we can pull each actor's respective GUID as well as their parent’s and write that to a save file.

Then upon loading it we can first just initialize all our saved actors and their positions & rotations etc, after which we can re-attach them by finding their parents thus recreating the original hierarchy. While I was initially concerned inregards to save and load times, I found through testing the initial implementation that they were negligible. Would I have liked to have a better, more efficient system in place? Yes, absolutely. Would it be worth the extra production time? No, not at all.

Initially I had some trouble getting certain aspects of the growth system to work correctly. Namely the climbing was rather difficult as debugging my vector math in blueprints wasn’t exactly the most pleasant experience, and gravity was probably the most frustrating for a good few days. Even to this day there are some issues with branch settling that still need to be addressed.

With everything being done in blueprints there is of course quite a bit of overhead, and in general there are lots of quickly thrown in bits of blueprints that were meant to be temporary that have stuck around slowing things down. But arguably the biggest performance hog was that I’d ignorantly set up a double For Loop in the plant master when retrieving all empty available sockets to grow the next branch on when it wasn’t at all necessary. Once I uncovered this and quickly patched it we saw performance roughly triple. I have of course gone through and made other similar optimizations overtime.

Ideally I would’ve liked to rewrite the entire system in C++ for performance efficiency, although at the time I started developing it I didn’t have any extensive knowledge of C++, especially not integrating it with other things such as saving, and now we’re at a stage where the amount of refactoring required to re-intigrate a rewritten version would just be too high, and too big of a risk to the project.

Another key feature of Bonsai '98 is the Prop System, which enables players to bring their artistic vision to life by decorating their dioramas. This system gives players the freedom to customize their creations, enhancing the aesthetic and storytelling potential of their bonsai arrangements.

The way props are handled and saved follows a structure similar to the Growth System. Each prop is assigned a globally unique identifier (GUID) along with the GUID of its parent object. This allows us to reconstruct the scene’s hierarchy whenever props are loaded, ensuring that all decorations retain their correct positions and relationships.

Props are dynamically loaded into the prop menu from a Data Table, which contains:

- All available props in the game.

- Their respective categories (e.g., rocks, ornaments, environmental elements).

- Their unlock state.

- Additional metadata for UI and gameplay interactions.

Upon launching the game for the first time, a player progress save file is created. This file tracks unlock progress for various tree types, pots, and props, ensuring that players retain their earned items across sessions.

During gameplay, players unlock new props through progression mechanics, such as leveling up. When a new prop is unlocked:

- The save file is updated to reflect the newly unlocked state.

- The game ensures that the prop is now available in the prop menu for placement.

When launching the game after an update, the system checks for new props that were added post-update. If previously unregistered props exist, they are added to the save file with their default unlock state, ensuring that all new content integrates seamlessly without overwriting the player's progress.

This system provides a smooth and persistent customization experience, allowing players to continually expand their dioramas while keeping all decorations and unlocks intact across multiple sessions.